The 19th century is the time of industrialisation, in Italy and in Venice. A major economic and social reshaping remodelled the face of Italian handicraft. Production of high quality silk fabrics included.

Making the most of traditional manufactures

The 19th century, though, is characterised by Romanticism, as well: to its recovery of traditions, we owe the rebirth of traditional craft activities in Venice.

One of the manufactures saved from oblivion was weaving, which had experienced a serious crisis after the fall of the Republic of Venice, in 1797.

The reborn production of high quality silk fabrics

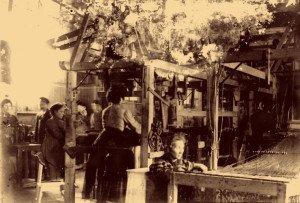

An element which contributed to this recovery was the Jacquard loom. After reaching the Veneto region towards the middle of the 19th century, this invention improved the chances of Venice’s textile production, because it made weaving faster and cheaper.

But the Jacquard loom led to rediscovering the value of fabrics made on handlooms, too: that’s how the Luigi Bevilacqua went over its knowledge on soprarizzo velvet again.

To produce it, though, the weaving mill needed skilled weavers.

Learning how to weave luxury furnishing fabrics and other Italian handmade fabrics

At Tessitura Bevilacqua, 19th-century weavers followed this path:

- they were friends or relatives of other workers: that’s how the weaving mill could be sure they were irreproachable. And that’s why our registers burst with the same family names and places of origin – most of all Cannaregio, the district where the weaving mill was located before moving to Santa Croce. And they were quite young: usually between 9 and 10 years old;

- first of all, they had to help an experienced weaver and, while observing her, they learnt the job;

- after 4 or 5 years, the girl became a textile apprentice: she worked for 3 years on a damask loom. This was both the easiest-to-use and the heaviest loom: the goal was to provide her with a physical training, as well. Now she was officially employed;

- as soon as she proved to be skilled enough, she became a weaver, and she usually covered that role for all her life. It wasn’t, indeed, a mere way to bring home some more money: being a weaver was a real job, for women.