Being a supercentenarian has its advantages. Most of all if you’re a business. The Tessiture Bevilacqua, which has been working in the textile field since 1700, has been more than one hundred years old for some time now. And in January 2015, its considerable age was officially recognised, because it became one of the Historical Companies of Italy. But why should a business producing Venetian fabrics own such a title?

A historical company producing Venetian fabrics

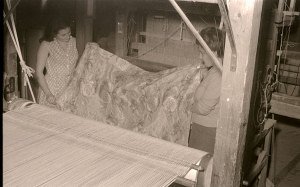

And this is exactly what let Luigi Bevilacqua keep on its journey from the 18th century till now. When Luigi Bevilacqua and his associate Giovanni Battista Gianoglio opened their textile factory, in 1875 in Venice, they saved the looms of the School of Silk. This had previously been closed – as all of the other weaving mills in the city – by Napoleon, who wanted to protect French production. Besides, Bevilacqua and Gianoglio decided to use a machine which had been invented at the beginning of the century, the Jacquard machine, to make production a lot faster. The quality of Venetian velvets, though, remained the same.

Centuries later, our company still uses the same looms and the same revolutionary machines to produce luxury fabrics. But now mechanical production backs up the manual one, in order to keep up with our clients’ requests.

Passing on tradition

In a world dominated by the industrial production of upholstery fabrics, we therefore had to make some changes, too. For example, the training period for our weavers is no longer two years,

And, now as then, here knowledge is passed on from a generation to the next: if in the 20th century daughters came here to help their mothers working on looms and thus learnt their job, now it’s the weavers on the threshold of retirement who train the new generation.

This is how we make what the Register of Italian Historical Companies itself aims at: saving a piece of Italian history.