Silk velvet is a unique, soft and lustrous fabric that found one of its main production centers in Venice, thanks to its intense trade with the Orient. It is estimated that in the 16th century there were at least 6,000 looms in the city dedicated to the production of the famous Venetian velvet. Tessitura Luigi Bevilacqua continues this tradition of the highest quality and uniqueness, still producing silk velvets with ancient looms and using the same craftsmanship techniques as in the past.

In this article we will tell you the history of this precious fabric, so that you can know it better and distinguish it: from the origins of silk in Italy, to its processing, to the different types of velvet according to the yarns used in its composition.

The Origins of Silk in Italy

Around 2700 B.C., silkworms were bred exclusively in China, where the silk industry was born. It is not entirely clear how silk arrived in Europe, but it seems that in 53 B.C. the Romans came into contact with this precious material, unknown to them, during the battle of Carre (today’s Harran in Turkey). There they clashed with the Parthians (inhabitants of ancient Syria), who waved silk banners.

From that time on, Rome began to import silk from China along the Silk Road, not buying it directly from the Seri (the Chinese), but through intermediaries belonging to other peoples. However, the origin and processing of silk remained a mystery. Pliny the Elder, in his treatise Naturalis Historia, described it as lanicium silvarum, or “yarn of the forests,” assuming that it was obtained from plants.

Silk Velvet Production in Venice

Emperor Justinian sent two monks on a secret mission to China to unlock the secrets of silk. They returned with silkworms, marking the beginning of silk production in Europe, although imports from the East continued. Marco Polo (1254-1324) was one of the first Westerners to reach China, traveling along the Silk Road, an intricate network of routes connecting East Asia, particularly China, with the Middle East and Europe. From his travels he brought back to Venice spices, precious artifacts and, above all, textiles: it was the fine silk fabrics that contributed to the fortunes of Venetian merchants, as well as those of Florence, Genoa and Lucca.

In the 16th century, Venice became a center of excellence in the production of silk velvet, marking the peak of silk art in Italy.

The Bevilacqua family, active in the textile arts since 1499, contributed to the development of this tradition, although Tessitura Luigi Bevilacqua was not officially founded until 1875. The company was located in a palace on the Fondamenta San Lorenzo, the former home of the Scuola della Seta della Serenissima, which had been abandoned at the beginning of the century following the Napoleonic decree of 1806, which sanctioned the closure of all artisan guilds in Venice.

What is Silk Velvet Made of?

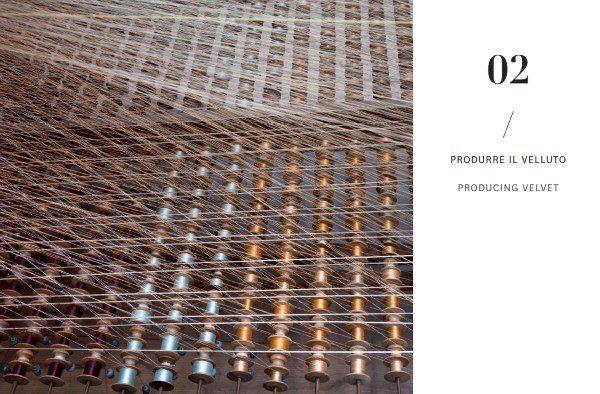

The element that distinguishes velvets from all other fabrics is the pile, that soft surface that tickles your hands as soon as you brush it. It is the yarns chosen for the pile that determine the luster and softness of the final velvet. Velvets have at least two warps and one weft. The first warp, or ground warp, forms the base of the fabric and intertwines with the weft. In handlooms, the threads that make up the ground warp are rolled around the subbio, the large cylinder at the end of the wooden structure.

The other warp is the pile warp: its threads are wrapped around the needles to form the curly velvet, or cut to give life to the cut velvet. These threads come from the bobbins placed on the cantra, the frame placed under the loom.

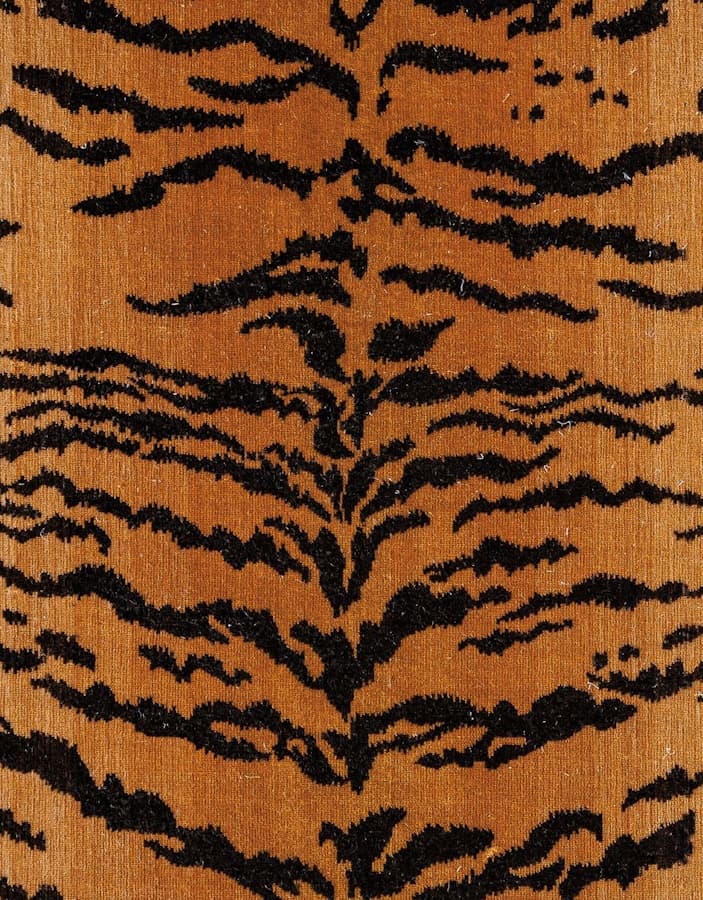

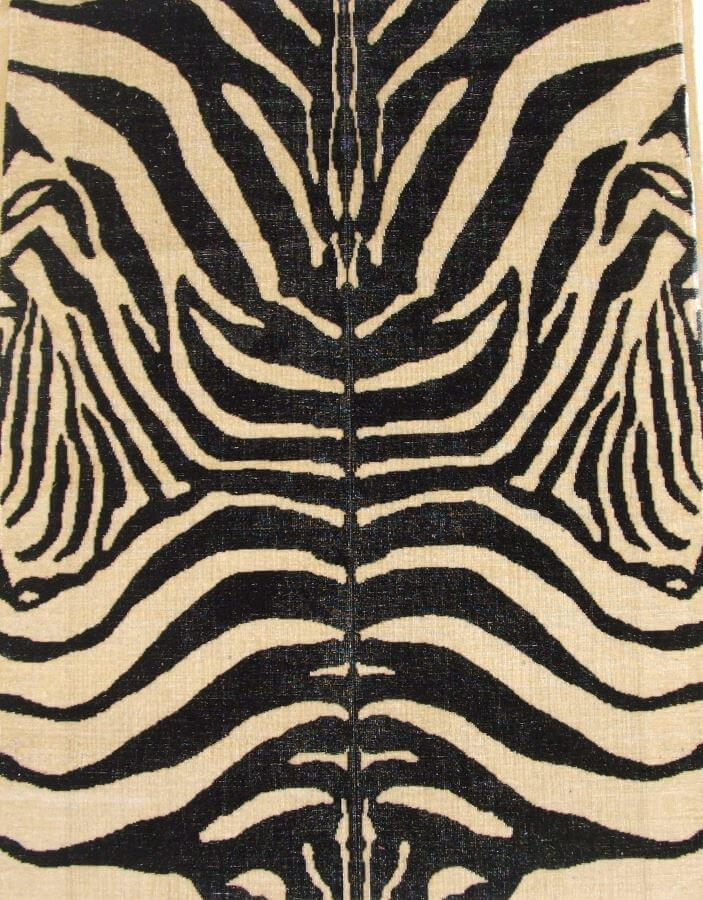

When we talk about “silk” velvet, we mean the thread used for the pile warp. In our handmade velvets, this is pure silk. For example, the composition of a velvet such as Giardino Fioroni Soprarizzo is 100% silk, both for the pile and the ground. Cotton and linen can also be used for the warp and weft of the ground, for greater strength. Linen is useful to make the weft stiffer, improving its performance and durability in upholstery velvets, such as Leopardo, Tigre and Zebra animalier cut velvets. The composition of these fabrics is actually 100% silk for the pile, while the backing is 70% silk and 30% cotton.

Soprarizzo Velvet Giardino Fioroni Production

Characteristics of Textile Fibers Used for Velvet

In addition to silk, other textile fibers can be used to create a velvet pile, and each of them gives particular results.

- Silk: is the yarn used to make the finest velvets, because it gives them a lustrous surface and allows them to fall very softly.

- Viscose: is extremely lustrous, giving velvet an extra touch of brightness.

- Linen: Gives velvet a more matte appearance. However, this fiber has the advantage of absorbing dyes very well, making colors appear more intense.

- Cotton: Gives velvet a more subdued sheen, but has the advantage of being very durable. However, the pile is shorter than that of silk velvet.

Sometimes the pile can combine different textile fibers, making it difficult to distinguish between velvets. In our fabrics, however, this only occurs in the weft or background warp.