The first fabrics produced in Venice were made of silk, woven with gold (or silver) threads via a manual procedure. The technique used to obtain these clothes of gold was revealed to La Serenissima thanks to the love of an emperor for a Venetian dame.

From the Fabrics Trade to the Silk Production in Venice

Since the beginning of the Christian Era, the West imported silk from China and Persia. Under Justinian, the processing of this yarn came to Byzantium, capital of the Eastern Roman Empire, a city with whom Venice had a strong trading relationship.

Venice had gained special privileges from Byzantium, such as the freedom of tax-free trading of all sorts of goods from the East. For this reason, it had the exclusive right to import luxury products such as spices, ivory and silk fabrics.

In addition to the trade of fine fabrics, local production of raw silk and its weaving later started, even if initially limited to simple patterns, without any embroidery.

The Oriental Influence on Silk Fabrics

Silk weaving techniques improved through time thanks to contact with other civilisations, mainly Chinese and Arabic, that had already been processing the fine yarn for centuries.

In particular, some fundamental processes for the production of clothes of gold were revealed to the local craftsmen by Antinope, an expert Greek weaver. He arrived in Venice with the court of the emperor Henry IV, who went there at the end of the XI century to venerate the relics of St. Mark’s body.

It is said that the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire fell in love with the noblewoman Polissena Michiel during his stay in Venice and he wanted to gift her with a beautiful silk and gold robe. For its realisation, he commissioned Antinope who, employing local artisans, taught them the technique.

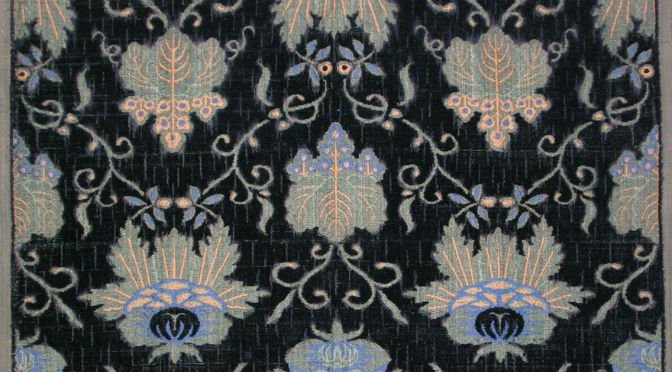

Another important contribution dates back to 1269 when the Polo brothers returned to Venice from their first journey to China. From this country they brought back several goods and fabrics, introducing Venice to certain technical weaving solutions and the typical Chinese decorations with plants and animals.

During the 1300s, there was a change in the decorating style, which left behind the old patterns, very regular and symmetrical, and started experimenting with lively and realistic images, decorated with botanic elements. Traditional Chinese allegorical symbols were adopted, including the lotus flower and leaves, the peony and fantastic animals, together with those of Christian symbolism such as the calf, the peacock and the parakeet, with vegetable connecting elements.

Also, the numerous skilful weavers who went to the Laguna from Lucca, between 1307 and 1320, largely contributed to the development of the Venetian silk art, especially regarding velvet making, of which they were true masters.

An example of a 12th-century fabric

The Rise of Velvet as the Status Symbol of the Venetian Aristocracy

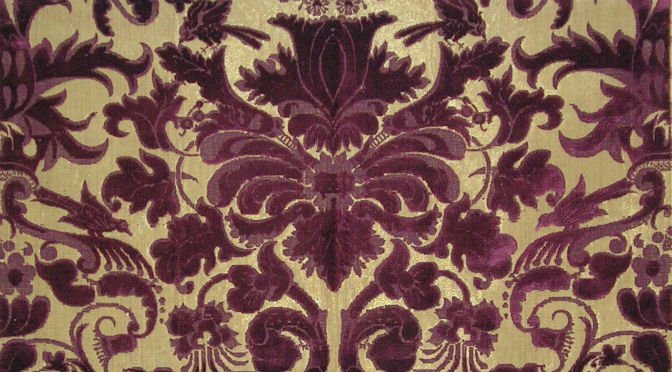

At the end of the 14th century, Venice witnessed the rise of velvet becoming one of the most requested luxurious fabrics. In particular, there was a type of decorated velvet called “afigurado”, in which the decoration is characterised by strong chromatic combinations and oriental elements such as the jagged leaf or the crowned palm frond. Artists like Jacopo Bellini and Pisanello contributed to the creation of such decorations.

A typical Venetian speciality was the alto-basso or controtagliato: a velvet, generally of an intense scarlet red with a surface made of various levels of thickness, decorated with concentric roses alternated vertically and horizontally with heraldic crowns sustained by the junction of two twisted branches.

This velvet, which remained unchanged for four centuries, became the status symbol of the highest social and political classes; the stoles worn by senators and the state prosecutor were made with it.

An example of a 14th-century fabric

Protectionist Policies Towards Venetian Textile Art

From the beginning of the 14th century, Venice began to regulate textile production, reaching a high level of quality. There was an institution, the Corte del Parangon, which was in charge of comparing the pieces of cloth used as a model and which had been carefully manufactured with the best materials available, with the new ones, before they were sold.

Venice was not allowed to import velvets and clothes of gold, except those from the Levant. Venetian master weavers were not allowed to work outside of Venice and slaves were not permitted to learn the art of weaving.

In 1366 a special commission was appointed, the so-called Sazo, in charge of monitoring the dyeing process. In particular, it set the rules for the production of the “chermes”, a unique nuance of crimson, later called scarlet or Venetian red. The dyers jealously kept the secret to obtain the particular colour brightness.

The production of velvet was also subject to controls and rules. Not all techniques were allowed, the tools for its processing had to respect specific rules, and the pieces had to have pre-established measures and to be labelled, as a guarantee of conformity.

16th – 17th Century: Decorations, Fine and Upholstery Fabrics

Around the end of the 16th century, the upholstery fabrics began to be separated from the clothing fabrics. The former was mainly used to decorate walls, produce curtains, to cover backs, seats, headboards and canopies.

Furnishing fabrics’ decorations were inspired by frescoes, bas-reliefs, church stained-glass windows, sculptures, friezes, horizontal strips, harmonious borders and above all grotesque like decorations which embellished them.

During the 17th century, the silk production in Venice began to diminish, even though the total turnover of the sector grew due to the shift of demand towards the beautiful fabrics, called “ganzi”, embellished with gold and silver and with sophisticated decorations.

An example of a 17th-century Venetian fabric

From the 18th to the 20th Century: Crisis and Rebirth of the Venetian Silk Art

The art of weaving maintained the refinement and sophistication of prestigious craftsmanship until the 18th century when the development of manufactures, mainly French, took over the European market.

In fact, the protection of quality through a constant and strict control had somehow jeopardised the Venetian entrepreneurship and strengthened the foreign competition, so that many textile factories had to close down.

The fall of the Venetian Republic in 1797 and, later on, the invention of the Jacquard loom, generated a deep crisis in the silk art sector, which nevertheless survived thanks to some historic manufacturers, until the 20th century, when it was restored to its former glory thanks to companies like Tessitura Bevilacqua.